As jau apie tai rasiau, kai buvo krize pries 10 m irgi atrode turejo visom kitom salim, bet ne Lietuvai , buti blgiausiai, o paliete blogiausiai ir ziauriasiai lietuvius....

net anekdota toki kazkas sukure tuo metu, skrenda krize per pasauli prasinesa per Prancuzija, Anglija, Vokietija, atskrenda i Lietuva ziuri apakus, sako,o kas cia prasinese

Sorry, aš tai ne anekdotais remiuosi, o sausais skaičiais, logika kaip tu mėgsti sakyti.

Išvis jūs buvot patys pirmieji subyrėję 2008 metais. Ir neišsikapanojot patys, o gavot kitų šalių ir ECB bei IMF pinigų. Ir, ne Lietuva yra linksniuojama kaip labiausiai nukentėjusi, o: Graikija, Portugalija, Airija, Ispanija ir Kipras.

Ireland[edit]

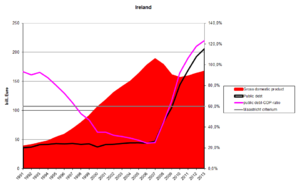

Debt of Ireland compared to eurozone average since 1999

The Irish sovereign debt crisis arose not from government over-spending, but from the state guaranteeing the six main Irish-based banks who had financed a property bubble. On 29 September 2008, Finance Minister Brian Lenihan Jnr issued a two-year guarantee to the banks' depositors and bondholders.[118] The guarantees were subsequently renewed for new deposits and bonds in a slightly different manner. In 2009, a National Asset Management Agency (NAMA) was created to acquire large property-related loans from the six banks at a market-related "long-term economic value".[119]

Irish banks had lost an estimated 100 billion euros, much of it related to defaulted loans to property developers and homeowners made in the midst of the property bubble, which burst around 2007. The economy collapsed during 2008. Unemployment rose from 4% in 2006 to 14% by 2010, while the national budget went from a surplus in 2007 to a deficit of 32% GDP in 2010, the highest in the history of the eurozone, despite austerity measures.[120][121]

With Ireland's credit rating falling rapidly in the face of mounting estimates of the banking losses, guaranteed depositors and bondholders cashed in during 2009–10, and especially after August 2010. (The necessary funds were borrowed from the central bank.) With yields on Irish Government debt rising rapidly, it was clear that the Government would have to seek assistance from the EU and IMF, resulting in a €67.5 billion "bailout" agreement of 29 November 2010[122] Together with additional €17.5 billion coming from Ireland's own reserves and pensions, the government received €85 billion,[123] of which up to €34 billion was to be used to support the country's failing financial sector (only about half of this was used in that way following stress tests conducted in 2011).[124] In return the government agreed to reduce its budget deficit to below three per cent by 2015.[124] In April 2011, despite all the measures taken, Moody's downgraded the banks' debt to junk status.[125]

In July 2011, European leaders agreed to cut the interest rate that Ireland was paying on its EU/IMF bailout loan from around 6% to between 3.5% and 4% and to double the loan time to 15 years. The move was expected to save the country between 600–700 million euros per year.[126] On 14 September 2011, in a move to further ease Ireland's difficult financial situation, the European Commission announced it would cut the interest rate on its €22.5 billion loan coming from the European Financial Stability Mechanism, down to 2.59 per cent—which is the interest rate the EU itself pays to borrow from financial markets.[127]

The Euro Plus Monitor report from November 2011 attests to Ireland's vast progress in dealing with its financial crisis, expecting the country to stand on its own feet again and finance itself without any external support from the second half of 2012 onwards.[128] According to the Centre for Economics and Business Research Ireland's export-led recovery "will gradually pull its economy out of its trough". As a result of the improved economic outlook, the cost of 10-year government bonds has fallen from its record high at 12% in mid July 2011 to below 4% in 2013 (see the graph "Long-term Interest Rates").

On 26 July 2012, for the first time since September 2010, Ireland was able to return to the financial markets, selling over €5 billion in long-term government debt, with an interest rate of 5.9% for the 5-year bonds and 6.1% for the 8-year bonds at sale.[129] In December 2013, after three years on financial life support, Ireland finally left the EU/IMF bailout programme, although it retained a debt of €22.5 billion to the IMF; in August 2014, early repayment of €15 billion was being considered, which would save the country €375 million in surcharges.[130] Despite the end of the bailout the country's unemployment rate remains high and public sector wages are still around 20% lower than at the beginning of the crisis.[131] Government debt reached 123.7% of GDP in 2013.[132]

On 13 March 2013, Ireland managed to regain complete lending access on financial markets, when it successfully issued €5bn of 10-year maturity bonds at a yield of 4.3%.[133] Ireland ended its bailout programme as scheduled in December 2013, without any need for additional financial support.[110]